Tax Cuts Don’t Cause Higher Interest Rates: Round-Up the Usual Suspects

Tonight’s federal budget has the usual suspects (that means you, Chris Richardson) lining-up to tell us that any fiscal stimulus, whether in the form of tax cuts or new spending, will put upward pressure on interest rates. This would come as news to RBA Governor Macfarlane, who has told the House Economics Committee on at least two occasions that fiscal policy has not been a significant influence on monetary policy in recent years.

What made the government’s claims about interest rates during the last federal election campaign so silly was that the 17% mortgage interest rates of the late 1980s were in fact associated with much larger federal budget surpluses as a share of GDP than we have now. The 1988-89 underlying cash surplus was 1.8% of GDP. The best Peter Costello has engineered to date is an estimated 1.1%.

If anything, we would expect strong budget surpluses to be associated with higher interest rates, because both are a reflection of the strength of the economy. This is correlation, not causation. As a general rule, the budget balance is a very poor guide to interest rates, both over time and across countries. The industrialised country with the lowest interest rates in recent years has been Japan, which has also seen the worst fiscal deficits.

Readers are invited to submit entries for the silliest or most overwrought comment and analysis on the budget, either in comments or via email. A small prize may ensue for the best entry.

posted on 09 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

The RBA’s Historical Revisionism

The RBA’s quarterly Statement on Monetary Policy is something of a misnomer, because most of the document studiously avoids any discussion of monetary policy as such. Monetary policy gets at best a few lines describing recent policy actions (or lack of action). Another few lines contain a broadbrush inflation forecast, which is the bottom-line for policy and from which policy inferences can be made.

Even though the inflation forecast is made on a no policy change basis, there is a sense in which the inflation forecast is endogenous. It is unlikely the Bank would ever forecast inflation outside the target range in the SOMP, because by the time such a forecast made it into the quarterly Statement, the RBA would almost certainly have acted on that forecast with a change in interest rates. The May Statement was a case in point, with the inflation forecast left unchanged, largely because the RBA had already tightened earlier in the week.

It is surprising then that so many in the markets look to the Statement for an explicit policy bias, since more often than not, it has none. The May Statement contained a little exercise historical revisionism, in which the RBA sought to retrofit a bias that was far from apparent in recent SOMP’s. According to the May SOMP:

the Board had taken the view that the next move in interest rates was more likely to be up than down, and this was signalled in the Bank’s policy statements.

In a narrow sense, this is untrue. Both the November and February SOMP’s said that ‘the Board recognises that policy would need to respond in the event that demand or inflation pressures prove stronger than currently expected.’ This falls well short of an explicit tightening bias and is little more than a statement of the obvious.

It was left to Governor Macfarlane to make it explicit, firstly in off the cuff remarks in response to a question at an ABE dinner in December last year and again in testimony before the House Economics Committee in February. As we noted at the time, Labor MHR Dr Craig Emerson was astute enough to pick the discrepancy between the February Statement and Macfarlane’s testimony. So what started as little more than an obvious statement of risks in the November SOMP turned into a May tightening, without ever making its way into a SOMP as an explicit tightening bias.

The May tightening statement also noted that underlying inflation in Q1 was running at 2.75%. The only “underlying” measures of inflation running at around this rate in Q1 were the RBA’s statistical weighted median and trimmed mean series. The statistical series are sometimes referred to as the “RBA core” series, but only in the sense that the RBA constructs and publishes them. These measures seek to identify the central tendency of inflation, but are necessarily somewhat arbitrary in what they exclude. The exclusions-based analytical series calculated by the ABS have a stronger economic motivation, in that they exclude items which are known to be volatile or that are non-market determined.

The reason the median market economist gave only a 40% probability to a rate rise in May was that they were looking at the ABS exclusions-based core series, which was running at only 1.7% y/y in Q1. The RBA has given “underlying” inflation an Alice in Wonderland quality, in which underlying inflation means whatever the RBA chooses it to mean.

posted on 06 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Debunking the Myth of Low Household Saving

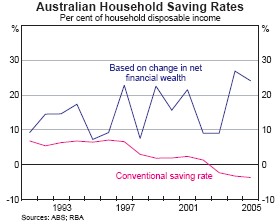

One of the more pernicious myths about the Australian and US economies is that their household sectors do not save and have lower saving rates than other industrialised countries. This largely reflects the much higher rates of household ownership of equities in Australia and the US than other countries, an important economic strength rather than weakness, but one that is not captured by conventional measures of household saving.

The RBA’s May Statement on Monetary Policy calculates a broader measure of household saving based on net financial wealth. As the RBA notes, this measure ‘presents a more realistic picture of Australian household saving behaviour than conventional measures.’ It shows a steady trend in household saving.

posted on 05 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(6) Comments | Permalink | Main

Ed Prescott at UNSW

2004 Nobel Prize in Economic Science winner Ed Prescott will be giving a lecture at UNSW on 1 June, titled ‘Unmeasured Investment and the 1990s US Boom.’ Here is the abstract:

During the 1990s, market hours in the United States rose dramatically. The rise in hours occurred as gross domestic product (GDP) per hour was declining relative to its historical trend, an occurrence that makes this boom unique, at least for the postwar U.S. economy. We find that expensed plus sweat investment was large during this period and critical for understanding the movements in hours and productivity. Expensed investments are expenditures that increase future profits but, by national accounting rules, are treated as operating expenses rather than capital expenditures. Sweat investments are uncompensated hours in a business made with the expectation of realizing capital gains when the business goes public or is sold. Incorporating expensed and sweat equity into an otherwise standard business cycle model, we find that there was rapid technological progress during the 1990s, causing a boom in market hours and actual productivity.

Follow the link for some related papers.

posted on 03 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Tax Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder

BCA President Michael Chaney in the WSJ, proving that international comparisons are what you make of them:

We are particularly concerned that there is no overarching plan or vision for Australia’s tax system…

Mr. Costello’s review, which has confirmed that key areas of the Australia’s tax system are not competitive and need immediate reform, provides the conceptual groundwork for a program of more comprehensive and sustained reform.

Unfortunately, Treasurer Costello intends the review as a rationalisation for inaction.

posted on 02 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

CNBC Burnout

With the big dollar rebounding after money honey Maria Bartiromo disclosed her conversation with Ben Bernanke, its time to review the Top 10 Reasons You Know You Watch Too Much CNBC.

posted on 02 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Australian Investment Aboard and the Current Account

An article in the most recent RBA Bulletin discusses the implications of a trend we have highlighted on this blog many times before: the growing stock of Australian investment abroad, particularly direct investment capital. Australia’s stock of foreign assets is growing faster than its stock of foreign liabilities. As the article notes:

Australia’s external assets are relatively skewed towards equities while liabilities are more skewed towards debt. As such, the valuation gains on assets in absolute terms on average exceed those on liabilities. One corollary of this is that the official measure of the current account deficit probably overstates the true ‘economic’ deficit, since the valuation gains are part of the overall return on foreign assets, but are not measured in the current account which includes only income flows…

In Australia’s case, if we were to treat the net valuation gains on foreign assets as all being part of the ‘income’ from these investments and include them in the current account, the current account deficit would have been on average about 0.3 percentage points of GDP per year lower than was actually recorded over the 15-year period.

The article also examines the implications of hedging for the change in Australia’s net foreign liabilities as a result of an exchange rate depreciation. The results make a nonsense of Nouriel Roubini’s recent forecast of a currency and financial crisis in the dollar bloc periphery.

posted on 01 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(7) Comments | Permalink | Main

Brad DeLong: Too Sexy for His Dressing Gown

Never mind bloggers in pyjamas, here Brad DeLong discusses the ‘mystery’ of US capital account dynamics - in his dressing gown!

When you have recovered from seeing Brad in his bath robe, see Pamela Anderson as you have never seen her before…on the Wall Street Journal op-ed page.

posted on 28 April 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The IMF & Global Imbalances

The WSJ editorialises on the IMF’s on-going fight against its own redundancy in a world of floating exchange rates and international capital mobility:

These are grim times at the International Monetary Fund; the world economy is too good. Global GDP has expanded by nearly 5% over the past three years, capital and trade are reaching far corners of the earth, and millions of the world’s poor are being lifted out of poverty. So naturally the IMF is worried.

That’s the backdrop of the weekend agreement in which the world’s developed nations agreed to give the Fund the task of lobbying to correct “global imbalances.” The idea is that the world’s trade and capital flows are out of whack, and are thus a grave threat to all of this prosperity. What the world needs now, said IMF Managing Director Rodrigo Rato, is “coordinated action” to unwind these “imbalances.” And who better to lead it but the Fund, through “multilateral surveillance” of problem countries.

There are few things more dangerous than a global bureaucracy looking to fix something that isn’t broken. Trade and capital flows are a function of millions of private decisions, so it’s far from clear that “imbalances” need addressing. Yes, the U.S. is importing huge amounts of capital and traded goods. But this is in part because the U.S. economy is growing so well, while Europe’s big three—Germany, France and Italy—are dead in the water. If Mr. Rato wants to roll a boulder up a hill, how about lobbying those countries to shape up?

posted on 27 April 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

While I Was Away

I have only recently returned from a few weeks in Europe. Thanks to all those who made it such an enjoyable trip. It was good to meet with some IE readers for the first time and to get some great first-hand insights into the UK and European economies. There was considerable interest in Australia’s experience with the housing cycle and other developments in the dollar bloc periphery.

While I was away, Treasurer Costello used the Hendy-Warburton report to remind us how wonderful the Australian taxation system is in comparison with the rest of the OECD. Having just visited some of the other OECD countries in question, I’m even more unmoved than usual by such lame comparisons.

The Treasurer’s accompanying press release noted that “The Report will stand as a significant reference point to assist in framing policy to improve taxation policy.” Yet the press release does not explicitly identify a single area in which Australian tax policy might actually be lacking.

posted on 27 April 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Peter Costello: Author of His Own Beauty

Dick Warburton and Peter Hendy as fig leaves for Treasury:

Late last month, the Treasurer appointed leading business figures Dick Warburton and Peter Hendy to conduct a study comparing Australia’s tax competitiveness with other nations.

But The Australian has learned that almost all the work is being done by a team of nine Treasury officials who are conducting the research and drafting the report in order to meet the April 3 deadline set by Mr Costello.

It is understood that the Treasury team has been sending Mr Warburton, the chairman of Caltex Australia and a former Reserve Bank director, and Mr Hendy, the chief executive of the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, drafts of chapters detailing their conclusions for the authors’ comments.

But it is understood Treasury failed to include some of the authors’ amendments and suggested changes in revised drafts.

Mr Warburton admitted yesterday that the report was being written by Treasury officials but said any comments he believed should be included would be in the report. “Peter Hendy and I would not have the time to write this material,” he told The Australian.

He defended the process as necessary given the tight deadline set by Mr Costello, which will allow the Treasurer to consider its findings before making any changes to the tax system in the May budget.

Mr Warburton and Mr Hendy were reviewing Treasury’s work yesterday, four days before the report’s Monday deadline.

Mr Warburton denied that the review’s independence was compromised by Treasury’s role in sourcing the evidentiary material. He agreed those involved in the review were working “long hours” but denied an overseas trip he is due to make next week had compromised the inquiry.

posted on 31 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Jagdish Bhagwati as Mobile Phone Neurotic

Should we be surprised when an adjunct scholar at a supposedly free market US think-tank writes a piece calling for regulatory attacks and litigation against mobile phone users and companies, simply because the author finds mobile phone use annoying?

This is what the AEI’s Jagdish Bhagwati proposes in an article in the FT. Bhagwati compares mobile phone use to bird flu, suggests mobile phone users are breaching human rights conventions and then turns vindictive, saying:

If providence were just, it would surely affect the brains of the users.

Bhagwati is a long-standing apologist for capital controls, belying his reputation as a defender of free trade and globalisation. He is also clearly neurotic.

posted on 30 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

A Roubini Forecast that is Dead on Arrival

It is not often you can dismiss a forecast as soon as it’s made, but Nouriel Roubini’s latest bit of doom-mongering is DOA. Nouriel suggests that Australia and New Zealand, among others, are set to experience a disruptive currency and financial crisis:

Runs on currency and liquid local assets may still occur with severe and disruptive effects on currency values, bond markets, equity markets and the housing market.

In the case of Australia and New Zealand, this prospect can be dismissed out of hand (I wouldn’t necessarily make this claim for some of the emerging market economies Nouriel lumps in with Australia and NZ). The best evidence against Roubini’s scenario is the experience of both countries in 2001, when the Australian and NZ dollars fell below 0.5000 and 0.4000 respectively. Not only was there no significant disruption to the domestic economy and financial markets of either country, the boost to competitiveness added to the strength of both economies. Nouriel’s assumption that a falling currency woud lead to a dumping of local currency-denominated assets by foreign investors didn’t play out then, not least because many foreign investors are significantly hedged against currency risk. The Australian and NZ dollars are currently falling in part because their debt markets are outperforming the US. If anything, a cheaper currency makes local asset markets even more attractive to fresh inflows of foreign capital.

In recent months, New Zealand authorities have not only welcomed a falling currency, they have even been actively trying to scare-off foreign investors - hardly the actions of a government worried about a currency crisis. The main risk to the NZ economy has been the domestic policy tightening that had seen the NZD trade weighted index to post-float record highs at the end of last year. An exchange rate driven easing in overall monetary conditions is exactly what NZ needs right now.

Roubini’s forecast in relation to Australia and NZ is also difficult to square with his bearishness on the US dollar. According to Nouriel:

U.S. policymakers - both at Treasury and even some, but not all, at the Fed - live in this LaLa Land dream that the U.S. current account deficits and fiscal deficits do not matter and that the U.S. external deficit is all caused by a global savings glut or is actually a “capital account surplus” as it allegedly represents the foreigners’ desire to hold U.S. assets. They - and financial markets and investors - may soon wake up from this unreal dream and face a nightmare where the U.S. looks like Iceland more than they have ever fathomed.

Roubini would have us believe that both the US dollar and the dollar bloc peripheral currencies are at risk, yet this would imply that the AUD-USD and NZD-USD exchange rates should remain relatively stable. It is even harder to envisage an Australian and NZ currency or financial crisis, when the most important exchange rate, that with the US, is largely stable.

Nouriel is the one living in LaLa Land.

posted on 29 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

The International Beauty Contest Treasurer Costello Doesn’t Want to Know About

While Peter Costello waits on the results of his international tax beauty contest, Andrew Ball in the FT (via The Australian) notes a recent paper by Eijffinger and Geraats, which:

found that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Swedish Riksbank and the Bank of England were the most transparent central banks. Next came the Bank of Canada, the European Central Bank and the Fed. Bringing up the rear were the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Bank of Japan and the Swiss National Bank.

The paper notes the RBA’s many shortcomings:

Although the Reserve Bank of Australia has adopted inflation targeting, it gets one of the lowest transparency scores (8, increasing to 9 in 2002) in our sample. Although the RBA gets the maximum score on political transparency, its openness on other aspects is much less. Economic transparency falls short because it does not publish quarterly data on capacity utilization and only provides rough short term forecasts for inflation (quarterly) and output (semiannually) without numerical details about the medium term. In addition, there was no explicit policy model until October 2001. Procedural transparency is low as the RBA does not release minutes and voting records. There is also scope for greater policy transparency because of the lack of an explicit policy inclination and a prompt explanation of each policy decision. Regarding operational transparency, the RBA provides neither a discussion of past forecast errors, nor an evaluation of the policy outcome. The Reserve Bank of Australia shows that inflation targeting by no means guarantees transparency in all respects.

The RBA’s published policy model (updated late last year) still carries the formal disclaimer that it does not represent the views of the RBA, so it is questionable whether it qualifies as an explicit policy model.

posted on 29 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

Setser’s Complaint

The Economist (or more specifically, Lexington) is insufficiently left-wing for Brad Setser:

Lexington could not find any public intellectuals (or ideas) from the center, the center-left or the left worthy of mention…I would say that the interesting policy debate on globalization currently is found on the left, not the right…The left takes seriously idea that the US needs to find ways to share the benefits of globalization more broadly and address growing concerns about economic insecurity and income volatility.

These are more homilies than serious ideas, but the notion that this burden necessarily falls on the United States goes to the heart of Brad’s misdiagnosis of issues such as global imbalances. Whatever institutional short-comings might be found in the US and other Anglo-American countries, it is the rest of the world, not the US, that needs to get its house in order.

posted on 29 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Page 76 of 97 pages ‹ First < 74 75 76 77 78 > Last ›

|